Viewpoint: Meritocracy and it's discontents

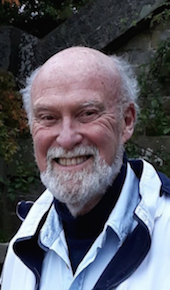

Professor Ian Linden

Ordinary people versus elites: call it populism, call it what you like, it's an addictive story especially for politicians. If 'the people' decide you are on their side and vote accordingly, you win. In the USA and Europe the story has begun to lose some of its electoral appeal but it has not gone away.

Michael Sandel's The Tyranny of Merit is one of the most important books of 2020. In his 1958 satirical critique The Rise of the Meritocracy the sociologist Michael Young ( later Lord Young of Dartington) introduced the term to describe a political system in which education, ability, talent, hard work and achievement are rewarded with wealth and power. Sandel also argues convincingly that meritocracy generates a sense of failure and exclusion in large groups of people. And that this sense of failure and exclusion fuels popular resentment and anger against elites.

The term meritocracy has rather faded but what it describes has become more prevalent. The populist opposition between people and elites accords with many people's social perception, experience, and their sense of how things are but lacks analysis of the causes of their strong feelings. Populism's rise has coincided with the decline of social democracy and its offer of equality of opportunity. That offer brought Tony Blair three terms in office and Obama two but ran out of steam in the last decade. Both Trump and Johnson are able communicators of the populist message "I am on your side against the elites". But why was social democracy's offer of equality of opportunity rejected?

Sandel goes beyond saying that for most people since the 1980s the 'American dream' has been just that, a dream. He takes the feelings of those whom the dream eludes seriously. If you believe there is a ladder available for you to climb out of poverty which you have failed to climb you feel a failure. Conversely if you're at the top of the ladder you feel your prosperity is deserved. You earned it by hard work and personal virtue. And those at the bottom suspect that the people at the top blame them, disapprove of them, regard them with disdain, to quote Hillary Clinton, as 'a basket of deplorables'. It is those feelings that populists exploit.

Sandel while a Rhodes scholar at Oxford was strongly influenced by the communitarianism of his Canadian philosophy professor, Charles Taylor. Sandel's own communitarianism challenges the individualist conceit that people succeed or fail as lone individuals so that those who succeed deserve their advantages. It is a belief that can only be sustained by ignoring the countless ways in which each person is shaped and influenced by their environment. The middle and upper-middle class have helpful social networks, private tutors and full book-shelves at home. The wealthiest have parents who can pay the fees at public schools which ease their way into Oxbridge or the US Ivy League. At the bottom of the ladder are children whose parents are too poor to take them to the theatre or on foreign holidays, too fatigued working at low-paid jobs to supervise homework, and may even be neglectful.

Sandel strongly makes the case that the great US divide in income is closely correlated with college education, or lack of it, what he calls 'the sorting machine'. He demonstrates how admission to the elite Ivy League US universities opens a fast-track to membership of the top 1% of wealthy individuals in the USA. "The children of poor and working class are about as unlikely to attend Harvard, Yale and Princeton as they were in 1954", he writes. Attempts are made by universities to counter this sorting machine, companies seek talent irrespective of 'credentialism', but little has changed in the US measure of merit over recent decades. Polling has shown an astonishing relationship between voting behaviour and educational attainment. The best predictor of a pro-Trump vote was lack of a college education. And who more adept at connecting with the shame and fury of those who felt themselves despised by a 'metropolitan elite', the denizens of the "Washington swamp".

In Britain, it is a Russell Group university education that opens the door to high-income jobs and provides the Oxbridge credentials for a specially privileged minority within a minority. Only 2% of Oxbridge admissions are white working class children. The 7% of children in private education take about a third of Oxbridge places. The Labour Party is losing the working class to Trump-lite politics while gaining the well-heeled and well educated in big cities. When security and prosperity are the 'merited' reward for an elite education, coinciding with years of wage stagnation and low incomes, the anger and humiliation of those who are not financially successful become socially and politically significant.

Sandel argues that poorly paid work and its contribution to society are undervalued in every sense. This began to be recognised when, for instance, during the pandemic bus drivers risked their lives to keep public transport going. If wealth remains the reward for elite education too little consideration is given to the emotions of those who do not attain it. Too little consideration is given to human dignity, to what Sandel calls 'contributive justice', being acknowledged as playing a constructive role in society with a voice that is listened to, which social democracy overshadowed by 'distributive justice'. "Finding ourselves in a society that prizes our talents is our good fortune, not our due", he writes. We haven't earned the attributes we are born and grow up with. We need the humility to acknowledge this. A society based on deliberation about the common good at the heart of its politics, rather than individual consumerism, will encourage practical solidarity. A meritocratic society is not culturally predisposed to do this.

So far, so chastening: Sandel with great gusto is sawing off the branch on which I and many friends have been sitting for the last sixty or more years. He has a chapter on the - Christian - moral history of merit in which he relates the unearned nature of our good fortune to the Christian understanding of Grace. He might have mentioned the no less sobering Catholic belief that the Kingdom of Heaven belongs to the poor in spirit - a kingdom where the division created by hubris, anger and humiliation are healed and human dignity restored. The G7 leaders who have been meeting in Cornwall need to have some of Sandel's critical vision of the future. Just an idle thought but it would be good if after all the self-congratulation they tucked into his book on the way home.

Professor Ian Linden is Visiting Professor at St Mary's University, Strawberry Hill, London. A past director of the Catholic Institute for International Relations, he was awarded a CMG for his work for human rights in 2000. He has also been an adviser on Europe and Justice and Peace issues to the Department of International Affairs of the Catholic Bishops Conference of England and Wales. Ian chairs a new charity for After-school schooling in Beirut for Syrian refugees and Lebanese kids in danger of dropping out partnering with CARITAS Lebanon and work on board of Las Casas Institute in Oxford with Richard Finn OP. His latest book was Global Catholicism published by Hurst in 2009.

See his website here: www.ianlinden.com