An Interview with Bruce Kent

The following interview was conducted by Professor Joseph Camilleri for Ideapod, a new website - www.thepowerofideas.com . It is reprinted with permission.

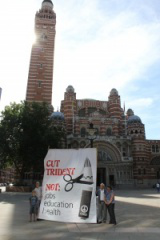

Bruce Kent has been one of Britain’s leading peace and disarmament advocates for over half a century, most recently with the Movement for the Abolition of War. He was recently engaged in a national 'Scrap Trident' tour of Britain. He is one of the thought leaders participating in Ideapod’s launch, promoting the “big idea” of world citizenship. Sign up for the waiting list at www.ideapod.com to share ideas related to promoting the cause of world citizenship.

Much of your life has been devoted to promoting the cause of peace and disarmament – tirelessly speaking, writing, organizing, protesting. How do you explain your unflagging enthusiasm and commitment? What is it that sustains your hope in the future?

My hope for the future? In part I suppose it is because so many apparently impossible positive changes have come about in the past. Why? Because a few people, often not well known, have struggled for change.

My hope in the future comes partly from this reality of history and in part because of my religious faith. I do not think this wonderful amazing world, of which we are part, is just some pointless inexplicable accident. I think there is a purpose and that I have some small part, in my time here, in helping to achieve that purpose.

Also I keep going because I am naturally obstinate and don’t see why stupidity and selfishness should be allowed to win.

One of your ongoing concerns has been the danger posed by nuclear weapons and the need to eliminate them. Reflecting on the efforts of the nuclear disarmament movement over the last several decades, what do you regard as its main achievements and failures?

It is now over sixty years since the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Yet there are still about 25,000 nuclear warheads in the world, held by some eight or nine countries. Some of these warheads are on systems at full alert – capable of being launched within a few moments once the order is given. Sixty years, and still this? That has to be a failure.

But successes there certainly have been. The 8/9 countries could well have been thirty countries but for pressure applied by our movements. No non state agent (terrorists we call them) has yet obtained a nuclear weapon. There have been large reductions in stockpiles. We now have a clear ruling from the International Court of Justice given in 1996 that negotiations aimed at the elimination of all nuclear weapons should begin, be conducted ‘in good faith’ and brought to a conclusion.

It is of course a failure that the ruling elites in the nuclear armed countries still think of nuclear weapons as the ultimate in global status, even though most realize that they have nothing to do with security but much to do with increasing insecurity.

Nearly a quarter of a century after the end of the Cold War, what is your assessment of the current situation – is it much different from what it was thirty or forty years ago? What is it that is preventing Russia and the United States from embarking on more drastic cuts to their nuclear arsenals?

The situation today is indeed different from that of the Cold War. Then the world was seized by extreme paranoia on the part of both superpowers each armed with absurd numbers of nuclear weapons. It was Robert McNamara who said we were saved by good luck and not by good judgment. Anyone who knows about the Petrov incident in the September of 1983 or the Cuba crisis of 1962 will know how close we have been to absolute disaster. The history of all those accidents and terrifying misunderstandings has yet to be written.

Today that immediate face-to-face confrontation has gone. Both Russia and the United States, after certain good housekeeping reductions, still hang onto their nuclear convictions and arsenals. Having told their citizens that nuclear weapons are the absolute guarantee of peace they would have some problems in telling them anything else. Both countries as well have thousands of professionals, scientists and civil servants who have invested their lives and their prestige in past thinking. They are all a force blocking change.

What of the other declared nuclear powers, and in particular Britain? Why is it that the British government finds it so difficult to relinquish its Trident nuclear program? Is it a case of powerful interests at play, or is it some emotional attachment to ‘UK pride and independence’, or simply bureaucratic inertia?

The difficulty facing any British government which would wish our country to cease to be a nuclear weapon state is a matter of history. Ernest Bevin at that time our Foreign Secretary, said at an inner cabinet meeting in 1947 that he did not mind what it cost. He wanted a nuclear weapon with ‘a bloody great Union Jack on top’

It is exactly that kind of nationalistic nonsense which has dominated British establishment and media thinking ever since.

Illusions have also been generated. One of the most prevailing is that Britain would not have a seat on the Security Council, if it gave up nuclear weapons. In fact when the Charter was signed in June 1945 only one country had nuclear weapons and they were yet to be used.

The media has constantly connived with this kind of thinking. The word ‘deterrent’ is endlessly used - a loaded word, not an argument. Our nuclear weapons did not deter the Argentinians from attacking the Falkland Islands.

To stop being a nuclear power would be ‘one sided’ disarmament is the constant accusation. Even North Korea is produced as a possible nuclear threat to this country.

All this has built up a climate which makes politicians fear that they will lose votes and power if they do not replace our current Trident missile system, however expensive it turns out to be.

Oddly when we gave up our chemical weapon systems independently, it caused not the slightest bother.

I know that you have been speaking extensively on the Trident issue in recent months. How would you describe the current public mood in Britain? Is it fair to say that nuclear weapons generally and Trident in particular does not feature prominently amongst the public’s current concerns?

I have been speaking in many parts of the country this year about the proposed £100,000,000,000 replacement of our current Trident system. It is true that the nuclear weapon issue globally is not a high priority with many of the public.

Many were under the impression, carefully nurtured, that the nuclear weapons threat had gone away. That is until our Prime Minister cited North Korea as a possible future threat to this country.

But what the public does very well understand is the vast cost involved in the Trident project.

Even though anti poverty and development lobbies do not stress, or even mention, the global military budget or even the British one, people do know well that in the current economic climate cuts to the health service, education, pensions, unemployment benefits and the like stand in stark contrast to this very expensive nuclear prestige project. Most people do not (yet) realize that to ensure that our country is nuclear armed (even with united States missiles) for another 30/40 years is an incitement to other countries to follow our lead.

Very few know that there is a negotiating process which could free the world of the nuclear weapon threat. Still less do they know how obstructive in this process our country has been?

In Scotland there is a strong majority against Tridents submarines or any replacement. So too in Wales. In England opposition is now well over 50 %. But our media never reflects this considerable swing in public opinion. As someone who has had a longstanding involvement with the Church, in particular the Catholic Church, how would you describe the Church’s theological and practical response to issues of peace and war? Is the Catholic Church and in particular its hierarchy providing the necessary leadership? If not, what, if anything, can be done about it?

In my Catholic church there is no shortage of top-level excellent statements about the immorality, futility and dangers of nuclear weapons .The call for their elimination has been clear. The link between military spending and poverty too has been well made.

Unhappily Pope John Paul II gave way to the pro nuclear weapons lobby when, in a much used 1982(3?) statement, he said something to the effect that the possession of nuclear weapons could be tolerated as long as there were serious efforts being made to get rid of them. That partly open door was swung wide by every national Hierarchy of a nuclear weapons state. No efforts were made to find out what negotiations were in progress or who was obstructing them.

Our own Cardinal Hume, a much respected figure, said in an article in our prestige newspaper, The Times, that from a moral point of view, if deterrence fails, we will move into a new situation. A correspondent the next day said he assumed that His Eminence meant heaven.

The top-level moral theology is there plainly enough. But the leadership at national level is missing.

Even the church poverty relief and aid agencies avoid mentioning, not just Trident, but all mention of the poverty- militarization link. The two papal encyclicals, Populorum Progressio and Pacem in Terris, might as well not have been written.

Here the Methodists, Baptist, Quakers and other Christian groups have been consistent and clear. So too have been the churches in Scotland. The Church of England and the Catholic Church are, as groups, still silent on the Trident issue though individual Bishops have made their objections clear.

I always wonder what the links are between Government agencies and major opinion forming bodies like churches. Secretly closer in fact than one would like to think.

Looking ahead to the next ten to twenty years, what are our most important tasks if the world is to become a more peaceful place in which to live? How well equipped do you think we are – spiritually, intellectually, organizationally – to take on these tasks? What might be the particular contribution of the younger generation?

I think we are well placed to help ‘to make the world a more peaceful place’. They are far from perfect but we do have global structures in place which were never dreamt of before. When one thinks of the world of the 19th century, when peace campaigners were working, again the odds, for some sort of established arbitration mechanism, we can see the progress that has been made. We now have a standing International Court of Justice. However defective it may still be, we do now have an International Criminal Court up and working.

The UN Charter and the Declaration of Human Rights are milestones in human history. Most of all we now have means of communication which can put us in touch with each other in ways impossible for past generations even to imagine. We also have a motivation which earlier generations did not have. We build peace and coexistence or we face wars in which there will be no victors. Only ash and radiation.

Bruce Kent was interviewed by Professor Emeritus Joseph A. Camilleri OAM, La Trobe University.

Note: Bruce Kent has been one of Britain’s leading peace and disarmament advocates for over half a century. Ordained a Catholic priest in 1958, he served for some 20 years as Chaplain of Pax Christi, Chaplain at London University (1966-74) and Parish Priest, Euston (1977-80). He retired from active ministry in February 1987.

In 1967 he launched a major correspondence in The Times about the morality of nuclear deterrence which produced much debate especially within the Churches. The same year he founded the Nigeria-Biafra Committee with the aim of ending arms supplies to both sides in a civil war, and flew to Biafra by night (1969) on a Joint Church Aid relief plane for a fact-finding mission.

In the early 1970s he set up COAT - Conscientious Objectors’ Advisory Team to promote recognition of the rights of conscientious objectors in all countries He helped to establish several campaigns: the Justice for Rhodesia Campaign; the Campaign against Arms Sales to South Africa, Christian Concern for Southern Africa, and the Campaign Against the Arms Trade. He was involved with several initiatives to promote reconciliation in Northern Ireland. In 1973 he became chairperson of War on Want. In 1975 he initiated the Prisoners’ Project which united organizations working for amnesty for prisoners of conscience and organizations working to improve conditions for other prisoners.

In 1980 he became General Secretary of the British Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. At the time of his leadership the Campaign grew from 2,000 to 100,000 national members and from about 30 active local groups to nearly 1000. In 1988 he undertook a peace walk of 1000 miles from Warsaw to Brussels (NATO) calling for a united peaceful nuclear-free Europe. He was actively involved throughout the 1980s in the European Nuclear Disarmament Campaign.

From 1985-1992 he succeeded the late Sean MacBride as President of the International Peace Bureau. In 2000, he addressed the first national meeting of the Indian anti-nuclear coalition in Delhi. One of Bruce Kent’s most recent initiatives is the Movement for the Abolition of War. In the summer of 2013 he undertook a national ‘Scrap Trident’ speaking Tour.