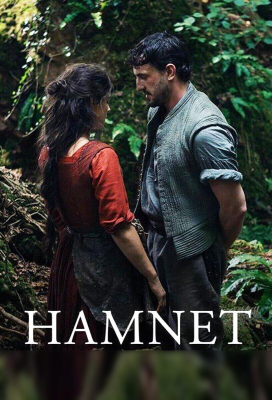

Hamnet

Helena Judd, from Radio Maria, reviews Hamnet, directed by Academy Award-winning filmmaker Chloé Zhao. The film has already won the 2025 Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) People's Choice Award, highlighting its critical acclaim and audience impact.

O for a Muse of fire, that would ascend

The brightest heaven of invention,

A kingdom for a stage, princes to act

And monarchs to behold the swelling scene!

These lines open Shakespeare's The Life of King Henry the Fifth. This prologue cries out my feelings after watching, Hamnet, the recently released film adaptation of Maggie O'Farrell's novel of the same name.

I have read the novel, and for much of the film I found myself yearning for what had been left behind. Yet the final scene almost persuaded me to forgive the director for the considerable slimming-down of O'Farrell's richly imagined story.

Jessie Buckley plays Agnes with fierce intensity. She is the film's true protagonist, later revealed to be the wife of William Shakespeare. Described as a "child of the forest", Agnes is governed by instinct and shaped by self-reliance. The early loss of her eccentric mother has forged her independence; she is accustomed to standing alone and drawing strength from within rather than from others.

The film departs significantly from the novel's timeline, a choice I found disappointing. Much of the novel's power lies in the imaginative threads that bind its characters together across time. Director Chloé Zhao shows little interest in sustaining these connections. Instead, the film unfolds in brief, episodic fragments. Scenes feel fleeting rather than continuous, creating a deliberate distance between the audience and the characters. We are not invited fully into their lives; we remain observers-almost detached witnesses.

This distance is especially apparent in the portrayal of Hamnet, the only son of Agnes and William. Unlike in the novel, we are not given sufficient time to grow attached to him. This is a deliberate artistic choice, reinforced by the fact that Zhao co-wrote the screenplay with O'Farrell herself. Hamnet becomes less a fully realised character and more a conduit through which we understand his parents. When he dies, I did weep-but I am unsure whether that grief arose from the film itself, my memory of the novel, or my empathy with Agnes's loss. My husband, who had not read the book, was far less moved.

While the novel left me somewhat distant from Agnes, the film brought me closer to her embodied experience. We never hear her inner thoughts in either the novel nor the film. Instead, Zhao allows the camera to dwell on Agnes's face and posture. The symmetrical, theatrical framing creates a kind of stage on which her worlds unfold: the expansive forest and the confined family home. The camera lingers, inviting contemplation rather than explanation.

As a Christian viewer, I could not help but interpret the camera's lingering presence as suggestive of God's presence-even if this was never the filmmakers' intention. Agnes's first labour is filmed from a great distance, as though accompaniment is withheld in response to her fierce independence. In her second labour, the camera draws closer as she finally accepts the help of her mother-in-law, crying out for her own dead mother and recognising, at last, that she cannot endure alone.

When Hamnet dies, the camera moves closer still. Agnes's grief is raw and almost feral. The room empties; no one comes near. She calls on neither God nor neighbour. Yet the camera remains. These scenes are powerful precisely because they are not rushed. Agnes chooses solitude, but death-silent and patient-lingers.

Zhao avoids rapid editing. Like theatre, the film favours the full body and the full gesture. A few gentle zooms and carefully composed shots allow moments for the viewer to breathe.

And yet, throughout the film, I found myself waiting for prayer, for hope, for even the smallest turn towards grace. This never quite arrives. Despite the historical context, faith is largely absent. Agnes's single outburst against the Church-spoken when she believes a newborn child has died-may be an expression of rage or a desperate attempt to draw another person into her pain.

For Christians, faith does not erase suffering; it anchors it. That anchor is notably absent here, and the resulting grief spills outwards-onto an audience who, like God within the film's own visual language, is never fully invited into the story.

William Shakespeare is in London when Hamnet dies. When he returns, his face is hollow, stunned rather than unloving. Again, the camera lingers, poised for connection. Yet the film denies this moment the depth it achieves in the novel, where O'Farrell writes of his grief with devastating precision. On screen, the opportunity for communion-between character and audience-is lost.

In both book and film, William retreats into work. He runs towards the theatre and away from the home where grief resides. Agnes attempts to control the uncontrollable; William disappears into his craft. Each chooses self-reliance. Each avoids the vulnerability of leaning on another.

Only in the final act does the connection between Hamnet and Hamlet fully emerge. William writes what he cannot say. The famous "To be, or not to be" soliloquy ceases to feel philosophical and becomes deeply personal-a father wrestling with mortality. In contemplating death, one wonders whether he is also searching, however unconsciously, for his Creator.

On stage, William is finally able to offer the farewell he never gave his son. The theatre becomes a shelter-a place where grief may be spoken and witnessed.

When Agnes enters the Globe, she resists becoming an audience member. She wants control. Gradually, she understands what the play reveals: William is grieving too. As Hamlet dies, Agnes reaches out her hand. Others do the same. In that moment, connection is restored-not through words, but through shared presence. Community forms, and with it, a quiet suggestion of grace.

At Mass, we remember salvation not alone but together. We listen, respond, stand, kneel, and sing as one body. Participation is active, embodied, communal.

Theatre, too, gathers us in shared light and darkness. Though we may sit in silence, the best performances move us together-sometimes even to tears. Shared pain becomes bearable when it is witnessed. This film understands that truth in its closing moments.

I left the cinema wanting to applaud-not for the film itself, but for the mystery of theatre. Like faith, theatre asks for presence, vulnerability, and communion. Whether Agnes and William are drawn any closer to a life of faith is left unresolved. Yet I would like to hope that having connected to the viewer at last, they may also learn to entrust themselves to a love beyond themselves.

I will end, as I began, with Shakespeare-from Henry V:

"God shall be my hope, my stay, my guide, and lantern to my feet."

Watch the official trailer here: www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y9Tv9wGPxIw