Access and Autism in Seminary Formation

The Teresianum - Wiki Image

Last week, 70 academics and practitioners from all over the world came together in Rome, to form a new global disability theology network, 'the Catholic Stream'. It aims to be the prophetic voice within the Church for differently abled people and their families. Further details about their plans will follow soon.

Mark Paine a permanent deacon of the Archdiocese of Birmingham gave the following address at the Teresianum, the Pontifical Theological Faculty and Pontifical Institute of Spirituality Teresianum in Rome.

My sisters and brothers in Christ, I stand before you today not as an expert who has all the answers, but as a wounded pilgrim who carries a mixture of pain and hope. I am Deacon Mark Paine. I have served for many years in Catholic education and parish ministry, I am Autistic, and I am a parent to Autistic children. I offer what I have learned in my own formation and ministry because I believe The Church must become a place where every mind and body can be formed, not in spite of difference, but through it.

For as long as I can remember, I have carried a steady, corrosive sense of wrongness - the thought that there was something defective in me. I try to hide that feeling by masking-by imitating what others expect me to do. Masking worked (sometimes) in public but it cost me everything in private. In a church context, simple actions in the sanctuary could become, and remain, battlegrounds of anxiety. Walking across the sanctuary, carrying a book, receiving a cue-each small liturgical task can leave me exhausted, ashamed, replaying mistakes for days.

I say this because formation is not only about learning doctrine and liturgy. Formation is about being known and held. In fact, true formation can only occur if this is the case. When I first entered formation for the permanent diaconate, I feared that my autism would be a deal-breaker. I worried that difference meant deficiency. The ever-present sense of inherent wrongness kicked in and I often wished to be told that I was not up to it. Every assessment, I expected to be told politely that I was not a suitable candidate for ordination.

Over time, I learned another truth: my neurodivergence did not disqualify me; it shaped how I hear God, how I attend to people, how I linger with those on the margins. Yet too often formation asked me to become someone else rather than becoming myself in Christ. That demand wounded me and hid gifts the Church needs.

We speak of formation as a shaping by grace into the image of Christ. Theologically, formation must be sacramental: it mediates God's mercy into bodies and minds. If that is so, then formation that excludes or marginalises parts of God's people is theologically incoherent. The Creator made each human mind as an expression of the divine image. To deny access to formation on the grounds of neurodiversity is to betray the doctrine that every person is made imago Dei.

To be formed is to take up a cross, to accept our brokenness and see therein the place where God's mercy meets us. But there is a difference between bearing a cross given by God and bearing the additional weight of institutional misunderstanding. When seminaries require masking as a litmus test of competence, they ask people to conceal their cross rather than to offer it to the Lord. Authentic formation turns our wounds into channels of grace, not reasons for exclusion.

When formation is not accessible, the consequences are real and painful. Candidates burn out. Talents are hidden. Parishes lose ministers who might have become bridges to families who feel excluded. Worse still, families learn that the Church is a place where they must perform to be loved. I have met parents who arrive at Mass with trepidation, expecting rebuke when a child cries. I have witnessed the relief in a father's face when his overwhelmed daughter was greeted with a smile instead of a stare. That relief is sacramental. It testifies that welcome is itself a form of incarnation.

I would rather be honest and say: my autism has not been a neat gift. It has brought crippling anxiety and shame. It has exhausted me to mask. But it has also given me a certain solidarity with those who are fragile, overlooked, or fearful. If God uses my awkwardness and my honesty to welcome one person into the heart of the Church, then that is ministry.

I am not suggesting that the formation team at St Mary's College, Oscott were wilfully or consciously making things difficult for me. Quite the contrary. They were unfailing supportive. However, as in most institutions and organisations, a lack of understanding of what neurodiversity actually is, and the various ways that we who are 'wired differently' interact with a neurotypical world, made the five year formation process difficult. It is my firm belief that clerical formation, or indeed any form of ecclesial activity can only be truly inclusive when those with lived experience are invited to speak their truth. We will have made progress when all voices are not only listened to, but actively sought out; not merely consulted, but placed at the centre of the decision-making process.

Formation must change in ways that are both practical and theological. I offer five invitations grounded in pastoral care and theological conviction.

1. Admit with Care and Listen

Make admission processes sensitive, invitational, and confidential. Ask questions that invite disclosure without penalising it. Begin formation by listening to the whole person.

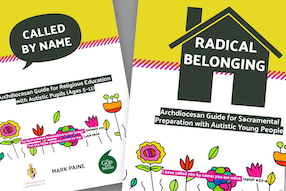

2. Create Sensory-Aware Formation Practices

Provide low-stimulus liturgy rehearsals, quiet rehearsal spaces, and predictable schedules. Teach liturgical roles in small groups where correction is gentle and expectations are clear. My liturgical training consisted of an hour watching a deacon go through a few actions such as how to proclaim the Gospel, and what to say sotto voce when cleaning the chalice at my final formation day. And what we were shown then had to be performed one at a time in front of all the other trainee-deacons. This is not exactly a gold-standard training method, particularly for those of us who are neurodivergent.

3. Replace Masking with Agreements

Co-create clear, written communication agreements about expectations, rhythms, and reasonable adjustments. Reduce the cognitive load of guessing unwritten norms.

4. Train Formators in Neurodiversity Literacy

Offer formation staff training in neurodiversity, so that differences are recognised, not pathologised. Equip supervisors to give strengths-based feedback and to spot signs of burnout.

5. Embed Rest as Formation

Make retreat, regulated quiet time, and sanctioned recovery days integral to the timetable rather than optional extras. Formation that exhausts is formation that fails to form.

These are not concessions; they are faithful practices that allow pastoral formation to be sacramental. They allow the seminary to embody the Church's conviction that formation is formation of whole persons.

Imagine seminarians whose different ways of knowing become resources for homily preparation, for catechesis, for pastoral planning. Imagine parishes where stimming hands are read as prayerful movement, where literal readings of scripture are treasured, where silence is honoured as a form of contemplation. Imagine formation houses where confession of weakness is met with prayer and practical support, not with suspicion.

This vision asks the majority to unlearn control and to risk vulnerability. It asks formators to move from assessing performative competence to nurturing sacramental accessibility. It asks The Church to embody mercy in structures as well as in words.

I genuinely believe that a Church which not only accepts vulnerability and difference, but actively embraces it, is a stronger Church. A better Church. A Church which is more fully aligned with Her mission. We should not be having conversations about the desirability and merits of disability inclusion in ten or even five years' time - the time to act is NOW. The time to embrace the synodal model and listen to those of us who have been out on the margins of the Church, or even excluded altogether, is NOW. The time for the Church to make disability inclusion as key a part of our diocesan, parish and school culture as safeguarding has become is NOW.

If my confession has revealed vulnerability, let it also reveal a pledge. I pledge to continue to speak for those who lack a voice within our formation houses, and within our parishes and schools. I pledge to work with seminarians, formators, and bishops to build pathways where difference is not a barrier but a door. I pledge to offer my own story-its failures and small mercies-so that another candidate might find a place to rest and find their own vocation, rather than a place to prove. Never again let a father feel too embarrassed to enter a church because of the way in which certain parishioners reacted to his beautiful daughter.

Let us pray for a Church that listens with patient ears and sees with tender eyes. Lord, give our formators wisdom and humility. Give our seminaries the courage to change. Give our communities the grace to welcome without requiring performance. Teach us to recognise the face of Christ in minds and bodies that think, move, and pray differently.

May our seminaries become schools of mercy where every candidate is formed not to hide their wound, but to bring it to the altar, to let it be touched by the healing hand of God, and to serve from that wound as a source of compassion.

May our parishes become places in which the dignity, the beauty and the sacredness of every individual is celebrated, every difference honoured as a gift. All of us are precious in the sight of God; all of us are passionately and totally loved by God; all of us are perfectly created as God meant us to be - our parishes, our seminaries, our Church need to reflect that reality.

Amen.