A moment of pure joy in Czechoslovakia: 30 years since the Velvet Revolution

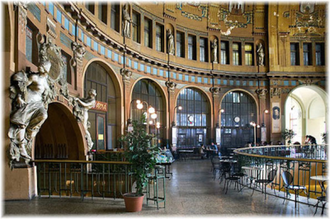

Main station, Prague

In 1981, Prague was firmly locked behind the Iron Curtain. In those days, few people in the West associated the Czech capital with charming medieval architecture.

Only the well-informed recalled the Prague Spring of 1968, when Alexander Dubcek, the Communist Party leader, tried to move the country toward what he called "socialism with a human face."

His attempts to loosen the chains brought a ferocious response from Moscow, and Dubcek was lucky not to be executed.

I was a frequent visitor in the 1980s. One of Prague's attractions was hearing Mozart performed in the same concert halls in which he premiered some of his greatest works. The annual Prague music festival featured dozens of concerts and operas, performed by world class artists in beautiful surroundings - and for a fraction of the cost of a seat in London or New York.

Vile though their governments were, the Communists made the arts and sport accessible; and their education systems sought out budding artists, writers, musicians, and athletes - just so long as they did not challenge the Party's hegemony. Since the Berlin Wall came down, some of these more positive aspects have been lost. We have globalised what Saul Bellow called a moronic inferno of materialism, individualism and trivia.

Back in 1981, Prague had an air of shabby gentility. Interesting people would deliberately avoid your eyes because they feared a conversation with a foreigner would land them in trouble with the authorities. They lined up outside stores, hunting for fresh food among the jars of pickled vegetables; they rode wheezing buses, and choked on toxic air. And they cautiously negotiated their way around a hypocritical system that pretended to be a workers' paradise.

At the Hotel Europa, an Art Deco gem on Wenceslas Square, you could swig Russian champagne at $1 a bottle, while listening to a melancholy trio playing Shubert and Chopin. At the nearby Alcron Hotel, another Deco triumph, the staff made little effort to hide the security services' tape machines at reception, recording guests' phone conversations. The museums, propagating their skewed version of history, were always empty, while the stark little bars in the suburbs were populated by solitary men getting drunk on the world's best pilsner lager at 10 pence a litre.

Yet, on the plus side, you could enjoy Mozart recitals in the garden of the house in which the composer stayed and worked when visiting Prague. Afterwards, we joined many in the audience who were heading to the Three Ostriches Restaurant for dinner; and then wandered across the Charles Bridge and up narrow, winding cobble stoned streets, lit by carriage lamps, through medieval squares and past Gothic masterpieces. These days, you fight your way through the selfie-snapping hoards. Then, culture-lovers had the place to themselves.

Over the years, we took buses to stunning medieval towns such as Bratislava, Ceske Budovice, Tabor and Kutna Hora. In the summer of 1989, when we visited Ceske Krumlov, we would never have guessed that a political earthquake was about to hit Czechoslovakia. That evening, after we had scoured the town for a restaurant that could produce any of the items optimistically listed on its menu, we returned to the disintegrating Potemkin Village of a hotel. Our room had an outer door, and an inner vestibule. As my husband shut the door between our bedroom and the inner vestibule, we heard a thud as the handle on the other side fell off. We were locked in our room, unable even to reach the bathroom. We tried to call reception, but the phone wasn't working. We opened the windows to shout down to passers-by, but they looked alarmed, as well they might, rushing away. We banged on the door, hoping someone would hear us. A German came out of his room and told us to be quiet, and then went away again. Eventually, a kind couple from Colorado came to our rescue, hunting down the illusive receptionist, who liberated us.

I still have a tatty piece of paper handed out to travellers as they departed Czechoslovakia. It listed the goods that would be subject to a tariff of 300% of their value, if you tried to export them. These included cider density meters, feathers, padlocks, knitting machines and bee keeping appliances. Moreover, the following were forbidden to be exported: meat grinders, tights, inner tubes and gas installation materials. It filled us with wonder that Communist Party officials had solemnly compiled these lists, imagining any tourist would wish to depart with these cutting-edge examples of Slavic technology.

It was with disbelief and joy that we watched the Communist edifice crumble during the autumn of 1989. The collapse was precipitated by a member of the European Parliament, Otto von Hapsburg, the man who would have been Konig und Kaiser, king and emperor, had the Astro-Hungarian empire survived. It is fitting that he should have been the prime mover in restoring the dignity of half of Europe. He announced he was holding a picnic on the Austria-Hungary border, and he pulled opened the fence. Thousands poured out of Hungary, and no one stopped them.

The playwright and often-imprisoned dissident, Vaclav Havel, formed the Civic Forum group. He convened open meetings at the Laterna Magika theatre in Prague, demanding the Communist authorities relax their grip on the country. The crowds supporting Civic Forum grew until hundreds of thousands were filling Wenceslas Square, night after night. At the beginning, the security forces killed protestors, but the Soviet leader, Gorbachev, hung the Czech Politburo out to dry, as he did the old men running East Germany, Poland, Romania, and Bulgaria in turn.

The leader of the Prague Spring, Alexander Dubcek, returned from internal exile. On one extraordinary evening, November 17th, Dubcek appeared before the crowd, alongside Havel, on a balcony above Wenceslas Square. He was love bombed by the people who had never forgotten his attempt to free them, back in 1968. He opened his arms and gestured that he was hugging them. By the end of the evening, the Politburo had resigned, and Czechoslovakia's Velvet Revolution had achieved its aim.

Havel was duly elected president, and Dubcek became the parliamentary speaker. He was only 70 when he died in 1992, but at least he lived to see the country he loved reclaim its place in our common European home. Watching the Velvet Revolution, and that remarkable night when people power swept aside the full force of the Soviet Union, was the single most intense burst of joy I have experienced. It was a wonderful time to be alive.

Austrian contrast

Back in the days before the Berlin Wall came down, we often returned to London from Czechoslovakia via Vienna, the epicentre of Hapsburg history. After weeks of empty shelves, sad window displays, and crumbling, brutalist concrete, it was a shock to cross into Austria: gently rolling fields dotted with healthy-looking, immaculate cows with bells around their necks; handsome farm houses straight out of Hansel and Gretel: clean rivers, and crisp, energising air.

Each neat, organized Austrian town had several cafes heaving with cream cakes and rich, lava-like hot chocolate; the most modest bed and breakfast provided a smooth little linen mat by your bed, to save your feet from touching the spotless floor; and at breakfast, there was a vast display of the best cold cuts, cheese, yoghurt, muesli, fresh fruit, preserves, breads and cakes you had ever encountered. After the tins of scary meat and the dusty bottles of pickled beetroot in Bohemia, it was enough to make you weep for the poor Czechs.

In Vienna, the senses were assaulted by Baroque opulence and gilded domes. Wandering along the Graben, we felt like wide-eyed country folk from the eighteenth century who had stumbled into the most advanced, wealthy and sophisticated city on earth; admiring wedding cake buildings that glowed with freshly white-washed plaster; passing stationary shops whose windows featured letterhead printed for the King of Jordan; and wondering at displays of shiny kitchen equipment of a quality unimaginable anywhere in points east, between Austria and Japan.

In the 1980s, Viennese cafes were often populated by wiry old ladies in fur coats, wearing green felt hats with feathers. They had tight little mouths like sphincters, and they frowned a great deal, despite the oblongs of dark chocolate that came, gratis, with each delicious cup of coffee.

Baffled by their sourness, my husband Henry and I mused that these ungrateful creatures were former concentration guards, or the widows of prominent Nazis. Clearly, their National Socialist dream society hadn't turned out quite as planned, so they glared at the young people with disapproval, and drowned their sorrows with einspanner mit dopple schlagsahne and wedges of Sacher torte, while their spoilt chihuahuas danced impatiently at their feet.

Vienna these days is all the better for the influx of immigrants (ironically from the former Hapsburg vassal states like Bosnia) and the generational wastage, as these judgmental women shuffled off to their Berchtesgaden in the sky. It is doubtful they reflected on the cruel paradox: the nation which had so enthusiastically embraced its native son, Adolf Hitler, remained free, while the Czechs (and the Poles, for that matter), were handed to Stalin in 1945.

Writing in 2019, it seems that the former Communist countries aren't the only ones failing to educate their children about the populist manipulation of propaganda that caused World War Two; wilful ignorance and intolerance is now found well beyond the countries of Eastern Europe. Unlike the Hapsburgs, who reputedly remembered everything but learned nothing, we remember nothing and also seem to have learned little from history.