Book: STOREY: A priest for his time

STOREY: A priest for his time by Peter Roebuck; Bookcase; £15; Pp 260

Many Sunday evenings in my early teenage years I would get on my bike and pedal a couple of miles outside our normal parish to go to Benediction at the Catholic church in the city centre of Kingston upon Hull. Those were the days of fasting from food and drink from midnight before communion, so there were no evening Masses. Religious faith was strong. We had no television to distract us, and so going to church twice on a Sunday was no hardship.

But I could not bear to be bored stiff by the droning sermons of the local priests, so rode to the church of St Charles Borromeo. Its classical revival front makes it hardly recognisable as a church, apart from a modest cross on top, probably because construction started the year before Catholic Emancipation in 1829. But inside there is an explosion of baroque. As the citation for the Grade 1 listing of the church noted: "Interior decoration: one of the most opulent and dramatic interiors of any C19 church in England and a nationally highly unusual example of Italian Baroque and Austrian Rococo styling."

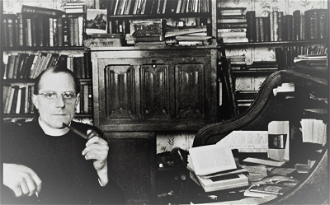

The colourful opulence was too much for my teenage eyes, though I was not there for the decoration, but in the hope of hearing Father Anthony Storey, one of the three priests, preach. He had a cut-glass English voice rarely heard outside a Church of England cathedral. But he also had the learning, imagination, wit and eloquence to take a commonplace reading and illustrate its meaning for today, with a message to take outside the church to the world.

As an intruder at St Charles, I never got to know him then. He became chaplain at Hull University, while I left Hull for university. Only in his final years when he retired to live 100 yards away from my parents' house did we really meet. I introduced him via a friend whom he baptised to Shusaku Endo, the agonised author of 'Silence', the story of Jesuits in Shogunate Japan. He always stopped to chat when we bumped into each other.

I remember him well into his 80s preaching at my parents' church, always thought provoking. He claimed, "God can sometimes be a bit of a bastard." I cherish a photograph of him, one of seven priests concelebrating my father's funeral Mass, standing tall and distinguished by his Roman nose and those outrageous sideburns, even though he was largely bald. At his own funeral St Charles was packed to overflowing, a testament to the widespread love of a long retired priest.

We should be grateful for this biography by Professor Peter Roebuck. I make a couple of quibbles. I never know anyone who called him "Storey". To my parents, he was always "Father Storey", though I am sure that Hull students called him "Father Tony", as Michael Hollings was revered as "Father Michael" at Oxford; "Storey" must be an accolade by Hull academics. Roebuck's prose is sometimes turgid, and he tackles this wonderful life largely chronologically, with endless facts crammed in.

Tony Storey had a privileged upbringing: he was born in rural East Yorkshire, the sixth of seven children of a land agent who worked for a great-niece of the Duke of Wellington; he went to Stonyhurst, the English College in Rome, back to Stonyhurst when the English College took refuge there in wartime, and, after ordination, to Cambridge University. From this sheltered start, he was plunged into the "complete new world" of struggling industrial Middlesbrough, where he learned to understand human beings and to see Jesus Christ in the most wretched circumstances.

He arrived in Hull a decade after the end of the Second World War and travelled the parish by bicycle, and was appalled at the poverty. Slum clearances had swept away the worst places, including the house in which I spent my infant years. Father Storey found: "Little side streets where there would be just one tap for the whole terrace and still the (night)soil clearance carts, the little buckets to be cleared away…

"Houses were infested very badly. The wallpaper had been put on again and again, so there were a lot of bugs behind the wallpaper. Sometimes the wallpaper would be 10 or 15 layers thick because they'd put a new one up… with flour and paste and the bugs would be living on that… " When called to give the last rites to a dying person, he often found, "lice all over the place in the bed and bed bugs too."

Our family was among the fortunate ones, nine people in a damp infested three-bedroom terrace house with an outside lavatory, but we had running water and a back boiler to heat it, wallpaper that was only four layers deep, and a frequent nurse visitor at school to check for head lice, but she never discovered any on any of us. Father Storey's account shows how recent and fragile is the prosperity that many people enjoy today, a warning to privileged opportunistic politicians not to play fast and loose with our lives.

Tony Storey lived tirelessly. At Hull University, where he was full-time chaplain for 10 years from 1962, he helped put Catholicism on the map, as well as helping thousands of young people through their cascading crises, Cuban missiles when we worried whether the world might end tomorrow, Pope Paul VI's Humanae Vitae encyclical, student protest and unrest.

He then went to Cottingham, which boasted being "the largest village in England", a well-heeled dormitory extension of Hull's urban sprawl. He expanded its boundaries and horizons to the world. He remodelled the church and set up a parish council to bring lay people into leadership. He was forever active in justice and peace issues, raising considerable sums for Bangladesh, Mozambique, Ethiopia, Peru, Cambodia, Brazil, and, above all, Sierra Leone, where Holy Cross, Cottingham, established a twinned parish.

His was not a life without struggle and pain. Father Storey fell madly in love with a schoolteacher. It was a chaste relationship, and largely conducted by mail since they were both busy people separated by distance. It caused both of them anguish, yet allowed him to understand the need for the Church to be more inclusive towards women. It was not easy to be university chaplain caught between impatient radical students and unimaginative bishops (as it wasn't for Michael Hollings at Oxford, Richard Incledon at Oxford and Cambridge, or indeed Bruce Kent at London). Father Storey was also subject to bouts of depression, which laid him low. But he emerged with his spirit and faith intact and ready to fight the good fight for the laity in the Church, for the environment and the Earth, and for burning issues of justice and peace.

Anthony Storey never received any advance in the church, no wisp of monsignorial purple, nor the cape of a canon, not even an upgrade to very reverend as a regional dean. When he was a young priest, Cardinal John Carmel Heenan was the dominant figure in the English church, of whom Peter Hebblethwaite memorably commented: "Cardinal Heenan was always appealing to Mrs Murphy in the front pews, and it would have been better for everyone if he had married Mrs Murphy."

The bishops of those days were more renowned for fidelity to Rome than for intellectual candlepower. Was Tony Storey ever considered as a bishop? Was it a failure of imagination - or a deliberate decision that he would not have been happy behind a dogmatic desk? I fear the former. How the English Catholic Church could have been rejuvenated by this man of deep piety, but immense humanity and wonderful understanding of the opportunities for Christ in a wounded world.

In a 2005 memoir, which Roebuck uses on his dedication page, Tony Storey wrote: "I never really found myself enamoured of the clerical set-up, I must say, and always felt myself slightly an outsider." Earlier, he had noted that he had been the last priest of the Middlesbrough diocese for 27 years to go to university. "I am regarded as one of those 'intellectuals' and quite openly spoken of as a threat and danger"; many of his colleagues, he added, were afraid of "the fantastic movements in world knowledge which our laity are sharing in, and our clergy hardly at all."

Anthony Storey's voice lives on. If you want to share a simple evening prayer, you can do so via Youtube:

www.youtube.com/watch?v=TI9lqJ_EDFc

More remarkable is a blustery recording on the Yorkshire moors of the 87 year old Tony Storey preaching at a remembrance for Blessed Nicholas Postgate. He begins: "The world and the planet are pretty badly flawed, and there's death and destruction all over the place and we see it all the time and all around us. And the message is that quietly it is going to be made right… The Gospel message is that there is no fulfilment without a good deal of bad suffering… Don't be afraid: all manner of things shall be well…"

https://middlesbrough-diocese.org.uk/fr-tony-storeys-ugthorpe-2006-homily/

His conclusion, a struggle against the wind, is to understand the evils of the modern world, and he mentions famine, refugees, and religious persecution, against the hope of Christ. His message is clear: "Always move forward. We are sent to be carers of the garden. The garden of God is this planet, and we are meant to be lifting it and bringing it towards wholeness. Christ's death for us means that we are able to bring it to wholeness, in our own small way…

"Absolutely every human person is a child of God, being created and loved at this moment... My life's work is looking after my garden and every human person…

"The open heart must be for the whole planet: for every single person is the object of my love and care, as fully as I can. I shall make a balls up of it, make all sorts of mistakes, get it wrong, over and over again… (and have to start again).

"I must walk with the Lord, be faithful to my prayer, faithful to the Eucharist and be faithful to having no fear: do not be afraid. All shall be well. All manner of things shall be well."

May he rest in pace; but may his restless spirit inspire us.

Kevin Rafferty was editor of The Universe, and raised its circulation from 105,000 to 119,000 copies a week, audited.

Storey: A Priest For His Time (pp xii+258, 30 illustrations) is priced £15 plus £4 P&P and is only available from the publisher Bookcase, 19 Castle Street, Carlisle CA3 8SY, bookcasecarlisle@aol.com, 01228 544560.