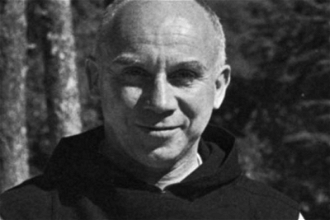

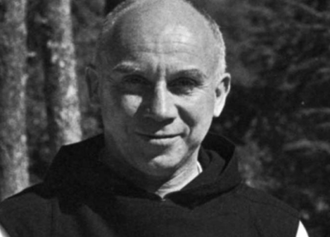

Thomas Merton & Alaska: A good match cut short

Source: CatholicAnchor.org

Thomas Merton lived as an imperfect monk in an imperfect world. For the uninitiated who may have hoped for definitive answers or prescriptions on living - they had come to the wrong monk. Merton, though much admired as a spiritual thinker, was equally admired for squarely facing many of his self-contradictions. He claimed he was nobody's answer to anything.

Father Richard Tero, pastor of Sacred Heart Church in Seward, has been a priest in Alaska for over 45 years. The well-regarded history buff believes Merton brought people back to the church. For four decades, Father Tero has passed along Merton's books as gifts to friends and prisoners to whom he's ministered.

"Nobody writes quite like Merton," Father Tero said, "and apparently, he needed to write everything! Yes, he was a flawed human being, but jovial, accessible. Not aloof and unapproachable. Hip with the times."

Father Carl Abele, 73, a former priest in the Anchorage Archdiocese for a few years beginning in 1969, and who now leads a semi-reclusive life in Florida and Ohio, spent his novitiate at Merton's Abbey of Gethsemani. He often saw Merton (also known as Father Louis) at the monastery's printing press. In a recent interview, Father Abele recalled seeing Merton wandering around the monastery's grounds lugging armfuls of books. Father Abele suspects it was often a ploy to discourage others from distracting Merton with random conversations.

After Merton's northern visit, Alaskan nuns reported that he possessed a great sense of humor, was totally relevant, yet completely simple. They saw him as a "groundbreaker in his efforts to learn about the spirituality of other religions." More conservative Alaskan Catholics at the time disagreed, believing Merton had no business exploring outside of his faith. The late Archbishop Francis Hurley in a 2007 unpublished interview joked that some people referred to Merton behind-the-scenes as "Father Malarkey."

Father Marc Dunaway of St. John Orthodox (Antiochian) Cathedral in Eagle River, shared how he first learned of Thomas Merton.

"I am embarrassed to say that as a young Protestant in the late 1970s, I would have been completely dismissive of him, especially given that he died at a Buddhist conference," he said. "Happily, my journey to Orthodoxy opened me to many new things."

When his mother, Barbara, an avid reader, came across the book - the journal - "Thomas Merton in Alaska" - they were surprised to discover the famous monk had visited the very property that was now St. John Orthodox Cathedral.

"Right away, a group of us decided to meet for breakfast once a week and read together Merton's 'New Seeds of Contemplation,'" Father Dunaway recalled.

He was especially encouraged by Merton's comments on God's sincere love for those who serve as priests.

"I feel humbled now that Father Louis's trek through life and ours hold in common the same quiet space in Eagle River," Father Dunaway said. "Who would have ever known such a thing would be but God alone? May God give rest to his soul among the saints."

Merton, as a beloved writer and a very modern "pedal to the metal" kind of monk, cannot be easily compartmentalized. He admitted his clouds of confusion about the world he "left" and the world of the 1960s, as he struggled to understand it from his more removed monastic vantage point. In his address to the U.S. Congress, Pope Francis shared a succinct but powerful insight about Thomas Merton extolling him as a monk who "challenged the certitudes of his day."

Some of the important questions Merton put to Alaskans included: What does a religious, a priest, a Catholic, a Christian stand for in this world? And in what way is a religious fully a person?

Wayne Pichon, of Anchorage, is a life-long Catholic and a founding member of the Alaska chapter of the International Thomas Merton Society. He is also a conference organizer for the upcoming Thomas Merton in Alaska event. He said the "world was ablaze in controversy, assassinations, and race riots when Merton showed up in Anchorage. Dissention was everywhere.

"This all weighed heavily on his mind," Pichon said. "He needed Alaska in that very moment."

Before embarking on international travels, the monk's new abbot stipulated that there should be no press coverage or TV, according to the Merton's official biographer, Michael Mott. This wasn't a problem at all in Alaska in 1968. No crowd of Catholics wanted to break down the church doors to mob the famous Thomas Merton.

Merton didn't lecture in the 49th state; he conversed. The archival recordings reveal that he spoke in a congenial voice, with spurts of laughter, and with great warmth, compassion and candor on a broad range of issues, in concert with his eclectic reading, including English mystics and Russian Orthodox theologians.

Merton's vast network of correspondents a few years before had included the controversial Russian novelist and poet, Boris Pasternak. Remarkably, Merton had corresponded with Pasternak immediately after his novel - Doctor Zhivago - was "illegally" released in the West. The 1958 novel - which won the Nobel Prize for Literature - ignited a political fireball creating an international incident and much embarrassment for the Soviets.

In his Alaska talk on "Prayer and Conscience," Merton aptly mentioned the Russians.

"When I pray, I am, in a certain sense, everybody," he said. "The mind that prays in me is more than my own mind, and the thoughts that come up in me are more than my own thoughts because this deep consciousness when I pray is a place of encounter between myself and God and between the common love of everybody."

He added: "More communion of souls and thoughts and consciousness - the Russians' idea of sobornost - a person being more than just an individual but in communion with others. Incidentally that's why I think the Russian way of prayer is maybe one of the best for us. Russian spirituality would probably be the most helpful thing to really start contemplatives grooving in this country."

As he spoke, not far away in the mountains above Anchorage, Nike Hercules Missiles could be launched toward any Soviet jets threatening Alaskan air space.

After the cultural repercussions prompted by the Second Vatican Council reforms, and its challenges for religious hierarchy and laity, Catholics raised many questions and asked for guidance about what the radical changes of the 1960s meant. The political turmoil of 1968 - the year that tore people apart physically and morally - greatly disturbed the peace, internally and externally.

Some of Merton's fellow priests, people such as the Jesuit, Father Daniel Berrigan, had made the headlines that year as anti-war peace activists arrested for entering draft offices and seizing and burning draft records. A recording of his meeting with an Alaska religious group captured Merton's admission that he was "mad at my friends about this." He elaborated: "I think they're nuts. They're ruining the peace movement."

Merton raised questions about social movements and agreed that "you have to be concerned about the world and politics in some way."

"But on the other hand," he added, "just aligning yourself with somebody else's movement is not necessarily the answer."

In his poignant Alaska talk, "Community, Politics & Contemplation," Merton's advice to religious about the de rigueur political ferment was to be "in-between: We shouldn't be on the conservative side and we shouldn't be on the radical side - we should be Christians. We should understand the principles that are involved and realize that we can't get involved in anything where there is not true Christian fellowship."

"You do have a great deal of good will in these movements, and you do have a kernel of desire for community, but power takes priority," Merton cautioned. "But the basic thing Gandhi said, and it has proved absolutely right, is that you can't have any real non-violence unless you have faith in God. If it isn't built on God, it isn't going to work, it isn't going to be real…"

In retrospect, one can say Alaska truly symbolized his unconventional spiritual quest - remote, with longer winters, more bears, and demanding survival skills needed. Like a holy mountain of spiritual spaciousness, Alaska was a place blessed with abundant natural wealth, and plenty of room for real, ideal solitude - the kind artists, homesteaders and hermits pine for.

By 1968, Merton felt he was "on his true way," fulfilling a great destiny. His overly-ambitious itinerary in Alaska, along with all his plans that followed to visit India, Thailand, Indonesia, and maybe Wales and Greece, represented more than a quickly thought-up trek to escape a few professional pressures. In his youth, he had done plenty of gallivanting in foreign countries. This was a strong desire, at age 53, to deepen his interior life after having lived the previous 27 years as a Trappist monk.

His serious intention to become more of an outright hermit once he concluded his travels, could perhaps be considered his just-reward for having produced more words than any other Trappist monk in world history. And for helping to keep the monastery's electric bill paid through his literary proceeds.

Merton's spiritual reconnaissance to Alaska demonstrated how open he was to new ideas and unknown lands. In trying to find the best route to a deeper inner life, to see through an unfiltered lens, he dreamed of touching another dimension, one that existed beyond volumes of words, piles of concepts, and theoretical systems and required more direct seeing. After he left Alaska, and headed to northern India, he made notes about the "majestic kind of mountain silence." Perhaps Alaska had offered his first real introduction to that scope of majestic mountain silence.

Located on the Pacific rim, Alaska was a crossroads of East and West, a geographic fact surely not lost on Merton. And Alaska's diverse presence of Native peoples and their pursuit of self-empowerment and self-determination would have richly fed his evolving concerns. Merton cared about the wisdom of indigenous cultures as captured in his posthumously published book, "Ishi Means Man."

Environmental awareness and ecological concerns were also concerns for Merton. He referenced nature approximately 1,800 times on the pages of his notebooks and journals.

For Merton, speaking off the radar screen for his entire 17-day journey to the 49th state was a blessing. He admitted to several locals that he liked to travel without his Roman collar, to permit more natural, less mechanical and stilted conversations with people he met along the way. Merton told Father Tom Connery how much he enjoyed fireplaces and throwing logs on the fire - for it settles you down and gives you peace.

Reverend Israel Nelson, a retired Presbyterian minister in Anchorage, once made a pilgrimage to Gethsemani to visit Merton's grave. As a seminarian, Nelson had discovered Merton at the suggestion of a Catholic friend. After reading "The Seven Story Mountain," he began to explore mystical Christianity.

"Merton's untimely death while traveling in Asia was a great loss for the mystical tradition of Alaska," Nelson reflected. "One can only speculate what spiritual insights he might have gained from an intensive study of Alaska Native spirituality. Had he succeeded in establishing a monastic community in Eagle River, there would, no doubt, have been a momentous enrichment of Alaska's spiritual development."

The writer lives in Anchorage and authored "We Are All Poets Here," a spiritual memoir involving Thomas Merton's 1968 Alaska journey. She can be reached at ktarralaska@gmail.com.