Text: Fr Martin Newell CP on faith and non-violent action

Fr Martin Newell CP gave a number of of presentations to the Passionist Justice, Peace and Integrity of Creation meeting in Rome last month. In the week which marks the 70th anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki - the text of his first talk follows below.

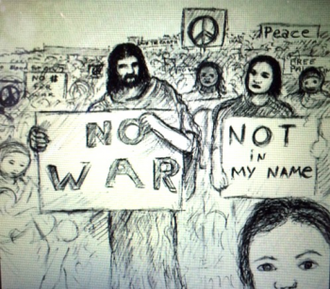

I am speaking here of my own experience and motivation. The first and most important basis of my motivation is my faith, and my conviction that Jesus is a pacifist, that Jesus is non-violent. This is revealed in his teachings and most powerfully in the Passion, where Jesus reveals at least two aspects related to this subject: Firstly, that the myth of Redemptive Suffering is true, not the Myth of Redemptive Violence. Secondly, that the love of God is a non-violent Love, as He observed when he said that God sends rain on the just and the unjust alike.

The second aspect of my motivation is the conviction that this does not mean that Jesus was passive. Jesus actively confronted injustice and the powerful in his life and ministry. And specifically, he also broke the 'Law' as it was interpreted in his time. Not that this is of the essence of non-violence, but it is essential to be able to challenge 'the system', the 'powers and principalities' in a way that breaks out of our and their comfort zone of what is widely considered as acceptable - in the right ways of course.

For example, he defended his disciples taking and eating ears of corn on the Sabbath. He regularly healed people on the Sabbath (Mark - man with the withered hand) - and specifically chose to do such a thing - on the Sabbath - in the synagogue - in front of the gathered community and the local leaders. He could presumably have waited. He wasn't even asked - it has been pointed out that in other healings, those in need asked Jesus to do so - on these occasions, it was Jesus who took the initiative.

These ways of reading scripture encourage and inspire me to follow the example of Jesus in confronting the authorities, the powerful, in my time and place, with non-violent direct action and civil disobedience.

More currently, it has been particularly the witness and example of Catholic Workers and those I have met through that movement, that have led me to certain practical actions. As a result, I have been arrested somewhere between 15 and 20 times, and have spent a total of about 8 months in prison, most of which was for a period of just over six months, back in 2000 / 2001. The issues we have confronted in these actions are mostly around war and preparations for war: the Iraq, Afghanistan invasions, the cause of freedom for East Timor, British nuclear weapons, the arms trade, military drones, military recruitment generally. I have also been associated with non-violent protests relating to asylum and immigration policies, minimum wages, and climate change. I believe in the UK, helping destitute asylum seekers to remain in the country, who been given a deportation order to leave, is technically an offence, although I have not known anyone be prosecuted for it.

The most dramatic non-violent direct action I have taken part in was the 'Jubilee Ploughshares 2000' action in November 2000. This was in the tradition of the faith based 'Ploughshares movement' and part of the British 'Trident Ploughshares' campaign. We hammered on a nuclear weapons convoy vehicle and put it out of action for six months, spending over 6 months also in prison.

My main motivation in terms of current analysis is that we, as British people, as western Europeans, as '1st World' people, are members of the privileged class globally. These weapons systems and wars are used to maintain our riches, privileges and comforts, at the expense of the lives and impoverishment of the poor elsewhere. This is true since the flip side of Pope Paul VI's statement "If you want peace, work for justice" is "if you want to prepare for injustice and violence, prepare for war." This is true even where the weapons are not 'fired', for example nuclear weapons. As in an armed robbery, the threat of use is usually enough.

The truth of this analysis, and the truth that peace and justice are just the two sides of the same coin, as are violence and injustice, was shown to me particularly clearly in the case of East Timor. This was a case of invasion and oppression of a small and weak country by its large and powerful neighbour, Indonesia - a matter of injustice. However, in the UK, when I got involved with the then Liverpool Catholic Worker and the Timorese refugees living there, I found myself taking direct action at a British Aerospace factory where they made Hawk jet planes which were being exported to Indonesia and used over East Timor. A matter of the arms trade, apparently. And the bigger and more powerful country of course had to prepare for that war, like all other wars. And it is the large, wealthy and powerful who win such wars, since they have the resources to be able to step up to the next level of violence. The US military even have a name for it in their military doctrine, 'escalation dominance'. The 'highest' level of violence is of course the nuclear option. And it is what the Roman's did when faced with the Jewish Revolt: they stepped up to the next level of violence, and completely destroyed Jerusalem and the Jewish nation.

Christians and Empire today

Jesus as we know, was born on the fringes of a small country, which was itself on the fringes of a large empire. He taught his followers ways of maintaining their dignity and freedom in the face of what was, in any conceivable future as far as the people of his time were concerned, insurmountable oppression. They only hope they could see was that God would send a Messiah who would miraculously change the pecking order, and put them on top. But the Messiah was not like that.

So what would Jesus have had to say to followers who lived in Rome and who were Romans citizens? St Paul was of course one of those, and he spent most of his time in Rome in prison, before being executed, as were many other Christians. This is relevant because this is my position, and the position of millions of other Christians who live in '1st World' countries, and it is especially important in the post-Christian or culturally-Christian 'west'.

We are called, as Daniel Berrigan said, to a practice and a theology of 'resistance to Empire', from its heartlands. We are called to live in solidarity with the poor and crucified on the margins of Empire, and the poor and neglected, who are also crucified in a different way, at its heart. We have similar freedoms to those Roman citizens had: they had a vote too, at least some of them. We are called to oppose the practices and policies of exploitation and oppression of the corporations and governments that have a presence in our countries. We are called to do this sacrificially, to follow the way of Jesus along the via crucis, to put our bodies in the way, to step out of our comfort zones. Its relatively safe for us, not unlike the way it was relatively safe for Roman citizens to ask questions. But on the edges of empire, the poor are still disposable and those who oppose the system are still executed.

One aspect of our contemporary reality in the West is that because of the developments of technology, they don't need our young men (or women) to fight their wars any more. All they need is our silence and our taxes. So non-violence has to go onto the front foot, we have to actively put our bodies in the way of the war machine and the corporate machine, we have to be willing to pay the price of our convictions. This is something people can see as authentic, not all talk and no action as the churches are so often seen to be. We also have to re-learn how to live simply, to live voluntary poverty with the poverty of the global poor in view, not the comforts, amnesia and sedation of the entertainment industry. We need to avoid being like Peter in the palace courtyard, warming our hands by the fire of minor privileges of empire, while offstage Christ's screams can be heard.

So, let's go live with the poor, lets campaign and organise, lets protest and resist, lets go to the global corporations offices or factory and protest, lets blockade, lock - on, occupy, sit on the roof, whatever it is that is both non-violent and morally legitimate, and at the same time not acceptable to business-as-usual, to the filthy rotten system and the established disorder. It might seem as if nothing can change, but the Roman Empire has long gone, and our faith in Jesus remains, and we know change does happen. To paraphrase one of my Diocesan seminary lecturers, 'if you don't wash your neck, it will just get more and more dirty.'

A HISTORY OF ACTIVE NON-VIOLENCE

For a comprehensive history in a short book, in the English language at least, I recommend "Non-Violence - The History of a Dangerous Idea" by Mark Kurlansky. Pax Christi in England also publish a pamphlet called "Nonviolence Works! - 60 nonviolent victories of the Past Century".

It is necessary to talk about active non-violence not least because pacif-ism is often confused with passiv-ism. It is certainly not the case that as Christians we can abdicate some responsibility for the course of history, for the prevention or at least resistance to evil in all its forms. We cannot be passive. On the other hand, it is not our job to save the world - God has already done that. Our vocation is to be faithful to God's call, to be truly and fully human as Jesus was, to be who we are called to be, children of God, so that we can truly reflect the face of God in whose image we are all created.

Those who call us to war, those who 'beat the drums of war', often portray the situation as one of impending doom, in apocalyptic terms. If we do not 'do something', the world is about to end, or at least the world as we know it. And that 'something' is defined as the most drastic thing possible, violence, war. And war and violence is believed to 'work'. Sometimes of course it does 'work', at least in the short term. Of course on the whole violence tends to work for those who are powerful in human terms, those who are wealthy and in control. It tends not to 'work' for the poor and the powerless, because they don't have enough resources, enough 'power'.

Non violence is powerful

They will also tell us that non-violence 'does not work'. But history is proving otherwise. As much as the 20th century was a century of violence and wars, it was also a century of non-violence. Non-violence is powerful. Non-violent struggles have changed the world. The Suffragist movement in the west brought votes for women. Gandhi's non-violence brought independence to India and fatally undermined the justification for Empires. Martin Luther-King's non-violence brought civil rights for U.S. blacks. Movements of nonviolent resistance were a key factor in the downfall of apartheid in South Africa, Communism in Russia and Eastern Europe, and the Marcos regime in the Philippines. Non-violent resistance movements played a key part in achieving independence for East Timor: I know because I played a very small part in that. Trident Plougshares and Faslane 365, the non-violent direct action wing of the British anti-nuclear movement, have played a key part in bringing the UK close to nuclear disarmament. I have also played a small part in that. And I know there were and are many others around the world.

That is not to say that non-violence will 'work' all the time. Nothing, humanly speaking, works all the time. Often the forces arrayed against it are just too great. Walter Wink suggests that non-violent resistance movements are in some ways like violent resistance movements: we are fighting a non-violent guerrilla war where the most important thing is not necessarily to fight or win a particular battle but to survive to fight another day.

Wink in his book "Engaging the Powers" ponders 'how' it works. In one sense, it is based on a faith in God or in human nature, that truth and love speak deeply to the human heart. That the exposure of injustice and violence to the light of truth makes it that much harder to continue. But Wink proposes specifically, based on some psychological insights that it is impossible for a person to experience wonder and hatred at the same time, and that this wonder is what is transformative.

He quotes two stories. One of a woman who woke up to find a strange and threatening man in her room. She started to talk to him and engage him, despite her deep fear. Eventually she felt he had begun to relax and relate to her, so she asked him to leave. He said he had nowhere to go, so she told him firmly he could sleep on the couch, she would give him and blanket and breakfast. She stayed awake trying to calm her nerves all night, and he left in the morning. Another true story tells of a Religious Sister living in a rough area of town, walking home on her own late at night. Hearing footsteps coming closer behind her, she realised she was being followed. She turned round and asked the man coming up behind her to carry her shopping bags. He obliged and walked her safely home.

On a side note, I suspect that wonder is a key experience in positive transformation of all kinds. Dorothy Day, quoting Dostoyevsky, said that "the world will be saved by beauty". The beauty that is meant is naturally not just physical beauty but moral and spiritual beauty too. Actions and words and people's spirit can be beautiful too. And perhaps it is beauty in all those forms that can provoke the response of wonder, of deep pondering that can lead us to a place we never knew existed. It is a truth we as Catholics should know: the Church has so often relied on the power of beauty: in church buildings and religious art, as well as in liturgy. Grace was a Zimbabwean woman who was staying with us at the London Catholic Worker some years ago. She used to go to both Pentecostal churches and sometimes Catholic churches too. I asked her what she thought, what her impressions were, of Catholic churches and services. She said they were 'beautiful' and 'dignified'. It was this beauty and wonder that brought Dorothy Day to conversion to Catholicism. And I do believe that beauty in all its forms can inspire us with the highest values and desires, as opposed to other things, like passionate preaching and speaking, which can inspire people in all kinds of ways, including to do the most despicable evil. In contrast, I believe true beauty can only inspire to what is good, beautiful and true.

Anyway, the point of that side track is to simply point out that this reliance on wonder is in a sense integral to our faith as Catholics.

I have my own personal experiences, not just of non-violence engagement in the context of political protest and faith based witness, but also in the in a sense more personal and equally vulnerable context of living and working among the crucified. I was mugged some years ago while living at the Catholic Worker. My training in non-violent instincts helped me to minimise the harm to myself and not give my attackers what they wanted (a group of teenage boys who wanted my mobile phone, in the dark alongside a canal). I did not involve the police on a matter of principle, in that I did not believe it would help break the cycle of violence. On the other hand, at one moment my non-violence broke down and I swore at the boys when they appeared to have given up, and that only made things worse for a while.

On another occasion I put myself between two guests at the Catholic Worker drop-in soup kitchen who were circling each other, one threatening the other and saying he had a knife in his bag, and the second one winding up the first. I knew them both, had a reasonable relationship with them. At one point I asked the first, Dean, "are you going to attack me". He said "of course not", so that gave me courage to keep putting myself between them. At this point there was no-one else in the hall I was in, and it seemed too late to get help. Again, I didn't want to call the police if I could avoid it at all, and any way by the time they arrived they would be too late. I did manage to defuse the situation, I was severely shaken afterwards, but my relationship with both those men was strengthened afterwards, and both of them were much less of a handful at the soup kitchen after that. Previously, they had both been among our most difficult 'customers'.

Another time at the soup kitchen, I had a big Polish guy, Alex, come swinging his fists at me as I was trying to get everyone to leave. He came closer until he was pretty much in my face. I stood there calmly and watched him. He then gave up and left. Later, another day, I heard him say to another guest, "Martin, he's a really good guy."

We also ran a community cafe in those years, Peters Cafe, in the crypt of St Peters Anglican Church. We had a customer, or guest, much like the men described above. He had a very aggressive air about him, and had a habit of using unwelcome suggestive language towards women and creating a hostile, unpleasant atmosphere generally, but for women in particular. He disappeared for a year or two and came back, starting along the same lines. I challenged him, perhaps not in the best way possible. He started arguing with me vociferously so I asked him to leave. He had me up against a wall at one point, while I was still asking him to leave. At one point he said, "If you shut up, I'll go." So I did, and he went. He didn't come back again. Once again, I didn't want to call the police, obviously I didn't want violence, but I didn't want to let him get away with it either. I could in fact have handled it better, but I believe my calmness and lack of obvious fear or overt anger helped.

In all these situations, I achieved my basic aim: preventing violence, protecting the vulnerable, and getting everyone out, without recourse to violence or force (eg calling the police). Either violence or calling the police could have had serious consequences for the continuance of the soup kitchen, for various reasons (Among others, it was held in a URC church building who had to consider their neighbours and other users). It would have also been extremely detrimental to the work of the cafe as safe place to come to. I also believe that there was a deeper outcome with those at the soup kitchen, that of a degree of conversion in the three men. They made much less trouble for us afterwards, and there was a respect from them for those of us who ran that place. It helped create an atmosphere of respect and trust so that we were able to continue to open up every Sunday to a group of people on what could have been called the 'front line', and was at times called the 'murder mile', in a very rough neighbourhood in Hackney, in the east end of London. Not that it was all a happy ending. Dean was stabbed and killed elsewhere some years later. I think Alex still attends the soup kitchen. Winston, the third, was put in prison after the London riots of [2010?] and when he came out he seemed to be a broken man, all the fight had gone out of him. Which you never know, might have been a good thing.

I am not an academic. Nor am I really a theorist of non-violence. I do have ideas about the best ways to engage with people in confrontational situations, both personal and political, but not such that I have worked them out systematically. But I have an increasing amount of experience that tells me this is true, as well as a continually growing confidence that this is both Gospel truth and a central dimension of the meaning of the Passion of Jesus Christ. And that is in addition to the plentiful evidence of the wider world.