Exhibition: The Real van Gogh: the Artist and his Letters

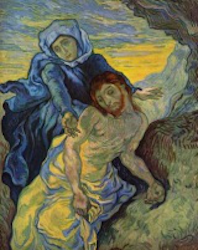

Van Gogh's Pietà (after Delacroix) painted in 1889 at the asylum in Saint-Rémy.

The first major exhibition of Vincent van Gogh's work to be shown in Britain for more than 40 years, opens at the Royal Academy on Saturday. The Real Van Gogh: the Artist and his Letters, features about 65 paintings, 40 drawings and letters, mostly to his brother Theo, that offer a wealth of new insights into the life of this great artist.

Beautifully curated across the RA's Main Galleries, by Ann Dumas, the show is arranged chronologically, with many letters reunited with the paintings to which they refer, for the first time, making the exhibition a unique chance to trace Van Gogh's development as an artist, guided by his own words. Dumas describes him as her "co-curator".

She said: "He is a wonderful writer. I can't think of any other artist who has written so comprehensively and intelligently about his own art."

There is something very intimate about seeing a person's handwriting. Van Gogh's is very legible. Sometimes you can see he is tired. There are crossings out, little notes and pictures. As he gets older his writing moves from a schoolboy script to a freer style.

In reading the letters one encounters not only a sensitive, determined and exceptionally hard-working man, but also someone possessed of a powerful intellect. This exhibition challenges the view that he was an erratic genius by allowing the viewer a rare insight into his artistic process through his correspondence.

Although Van Gogh was often ill and always poor, his letters rarely refer to suffering. They range from the prosaic - "Can you send me a few ordinary brushes as soon as possible?" - to poetic descriptions of landscapes he was painting. He "revels like a cicada" in the warm summer weather. There are also many references to art and literature - Van Gogh was fluent in English, German and French and read Shakespeare, Dickens, Zola and Maupassant in their original tongue.

Van Gogh was a late starter. He decided to try a career as an artist at the age of 27, after he had given up a job as an art dealer, failed a theology course and was rejected as a preacher (during his training in Belgium he gave away food, clothes and what little money he earned to the poor, and was sacked). In 1882 he went to the Hague and began teaching himself to draw - sketching landscapes with the help of a home-made 'perspective frame'. A few days later, he sent Theo a sketch showing him at work on a beach - a tiny figure looking out to sea through the frame, palette in hand, painting directly from nature.

By 1884, he was living with his parents in Neunen, sketching the peasants at work in the fields and determined to master the human form. He was also painting in oils. By the time he painted the autumn trees in 1885, he reported "a thawing in my palette".

When he moved to Paris in February 1886, that thaw burst into a glorious spring. Seeing the work of the Impressionists for the first time had a profound effect on him. By summer, he was painting Terrace in the Luxembourg Gardens in the delicate colours and looser brush strokes of Monet and Pissarro. Even more significant was the impact of the younger generation of artists - including Seurat and Signac with their innovative stippled technique. Van Gogh used this in a modified way in Grass and Butterflies.

Still learning voraciously, he moved to Arles in Provence, living in the Yellow House, where the sun-soaked landscapes of the south worked their magic. His colours intensified, the handling of paint became entirely his own. He walked miles into the surrounding countryside to paint orchards, cornfields, wide, sweeping vistas.

Portraiture was more important to him than any other genre. Using intense colours, in Arles he created a series of bold, confident portraits, among them: Self Portrait as an Artist and the Zouave. Often unable to find models he was delighted when he befriended the local postman and painted his entire family. He threw away his perspective frame. Ann Dumas says: "In Arles, he is writing less about the practicalities of painting. There's a sense that he can do it now."

Van Gogh dreamed of establishing an artists' colony, a "studio of the south" in the Yellow House, and in autumn 1888, when Paul Gauguin came to stay, it seemed that dream was coming true. However, after ten disasterous weeks, Gauguin left, and Van Gogh suffered his first serious mental breakdown. "He was always looking for intimacy," says Ann Dumas, "but perhaps he wasn't very good at it."

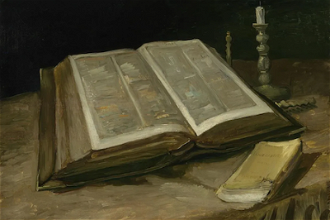

Van Gogh returned alone to the Yellow House in January 1889, after a short stay in hospital and in his first days there painted a thoughtful, telling picture. Still Life around a Plate of Onions, is the opening picture for the show because it is the only painting of his that contains a letter. The painting is like a self portrait. Van Gogh's dreams of an artistic collaboration with Gauguin had been shattered. He had come back alone to the Yellow House and was painting the ordinary objects around him: coffee, onions, a book.

Later that year, a further period of illness led to a longer stay in the asylum of St Paul-de-Mausole near Saint-Rémy, an old monastery where he was nursed by nuns. When he was well enough, he produced paintings based on some of his favourite artists, among them: Millet, Delacroix, and Rembrandt van Rijn.

Some of their religious subjects: Lazarus, The Good Samaritan and the Pieta (with red hair like Van Gogh) had a bearing on his difficult situation. He also managed to paint the view from his window, olive groves, with their undulating outlines, set against the backdrop of the Les Alpilles mountain range. He wrote to his sister that he was re-reading Shakespeare's historical plays. To Theo he expressed the hope that he would one day produce a series of 'Impressions of Provence'.

Frustrated at his lack of progress, in May 1890 he moved to the small town of Auvers-sur-Oise 20 miles northwest of Paris. He told Theo he felt a failure there. In his last 70 days he painted 70 canvasses, many of them among his most assured works - including a radiant vase of white roses included in the show. He wrote to Theo: "The whole crisis has disappeared like a thunderstorm and I'm working here with calm, unremitting ardour to give a last stroke of the brush."

In the last letter posted to Theo, written on July 23 1890, Vincent writes not of depression or anxiety but that he is applying himself to his canvas "with all my attention". He encloses a sketch of Wheat Fields After the Rain, which is one of the most serene pictures in the show.

Ann Dumas writes: "These radiant canvases demonstrate that at the end of his life van Gogh was a consummate artist in full possession of his powers. But ultimately the "full and fortifying" countryside was not enough to prevent him from taking his life. He died on 29 July 1890 at the age of 37, probably feeling he was a failure. His paintings sell for millions now but he only sold one in his lifetime.

The Real Van Gogh: The Man and His Letters, sponsored by BNY Mellon, is at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, 23 January until 18 April. Vincent Van Gogh - The Letters: The Complete Illustrated and Annotated Edition, is published by Thames & Hudson, and available online at: www.vangoghletters.org